Category: Longform

You are viewing all posts from this category, beginning with the most recent.

The Casual Vacancy by JK Rowling (Books 2023, 10) 📚

To tide me over until the new Strike book comes out (in just under two months) I suddenly decided to reread JK’s single non-pseudonymous, non-magical book. It’s over a decade old now, which is kind of hard to believe.

And it’s still bloody heartbreaking. How she can make us feel so much for so many flawed characters (but especially one or two) in so few words, never stops amazing me.

It’s a slice of small-town England, in which a parish council member dies, leaving the titular vacancy. And all that proceeds from that. It shouldn’t be as compelling as it is, based on that description. But there you go.

Barbie, 2023 - ★★★★½

Best musical moment for me: ‘Closer to Fine’ by the Indigo Girls, repeatedly. That was unexpected.

And overall, it’s a great movie.

Oppenheimer, 2023 - ★★★★

I’ve never seen the Hackney Picturehouse as busy as it was when we arrived last night. A rainy Monday in July, and it was packed. The Barbenheimer effect, of course. But I was there on the first weekend of Black Panther, I was at the opening night of the last Star Wars movie… Neither was as busy as this.

Oppenheimer was incredible. Hard to make out the dialogue, at times, of course, You expect that from Nolan, and we've maybe got worse at listening to screened entertainment, due to nearly always having the subtitles on at home.

But I didn't feel I missed anything too significant.Oppenheimer's story is quite incredible. I had the vague impression, since I knew only that he'd been instrumental in the Manhattan project, that he was more experimenter than theoretician, maybe an engineer, rather than a physicist. But it turns out (assuming the film and the book it's based on are right) that he was very much a theoretical physicist — even theorising about black holes — and very much not an experimentalist.

Later 'more politician now than scientist', as one of the many other characters says. And those other characters: so many names from the history of physics, many with parts so small you don't even realise they were there till you look at the cast list. Feynman, for example.

Heisenberg (I didn't know his politics were so uncertain); Bohr. Einstein, obviously, though he wasn't involved in the Manhattan Project.

Artistic license: how far were they from the trinity bomb, the initial test detonation? The longest distance they mentioned was twenty miles, for the longest-distance observers, and the closest 1000 yards. That must have been the blast radius, though: there's no way anyone was that close!

But as represented, the time between the light and the sound seemed ridiculously long. It created quite a chilling effect, though: I may never have experienced such a silence in a cinema.

Good film, would watch again. Preferably with subtititles.

Falling for Figaro, 2020 - ★★

A woman gives up her high-paid fund-management job in London to try to become an opera singer. You could probably write the rest.

This was what you might call a slight movie. It has some feeling of being a romcom, without much of either rom or com.

It was moderately funny in places. It has Joanna Lumley as a faded opera diva now teaching in the Scottish Highlands, after all.

Daniel Deronda by George Eliot (Books 2023, 9) 📚

I mentioned in May, that I had been reading this. It’s taken me till now to finish it.

In another sense it’s taken me a lot longer: I first started reading it in 2004. Back then I was doing an Open University literature course. In one module an extract from Daniel Deronda was one of the options for us to write about. I think I must have chosen it, because my tutor sung its praises, saying it was a great one to read over Christmas, ‘curled up next to the fire.’

So I bought it and started it at the time. I can be fairly sure of this, as the bookmarks I found in it, when I picked it up back in May, were a pair of old-school paper train tickets from 2004. Two markers, of course, because this is a classics edition with comprehensive endnotes.

The main bookmark was around page 200, so I got a decent way into it. Except this is a book of over 800 pages, so actually not that far. I don’t know why I stopped. Probably just got distracted by other books and petered out. I started from the beginning again this time, and found I remembered almost nothing of what I read nearly 20 years ago.

But enough meta story about my history with the book. What of the book itself?

It’s really two main interwoven stories. The title character appears briefly, wordlessly, in the first scene, and then is not seen again for the whole of the first book (it was originally published serially, and is internally divided into eight books). First we get the start of the story of Gwendolen Harleth, a young woman of fair but limited means, who might expect to marry well. Until her family falls into poverty.

Her story at times feels like it’s going to be a conventional, Austenesque romance. It is not, of course: it’s much more complex than that.

The other story is about how Daniel Deronda rescues a young Jewish woman from self-inflicted drowning, and finds her a home, and what follows from that. This section is largely about the way Jews were treated at the time (the 1870s), and the idea that they might seek a homeland. The start of Zionism, in effect. Deronda is sympathetic to the plight of the Jews generally, as he is to Mirah, the woman he rescued. But then, he’s synmpathetic to just about everyone.

The darkest part of this story shows us how terrifyingly restricted, locked down, controlled, a married woman could be in those times. Even if the husband in question is not physically violent, he simply controls all aspects of their lives, and hence her life. She has no hope of escape. It’s powerfully understated, and all the more chilling for that.

Some sentences are overly long by modern standards, and some of the language is complex or old-fashioned enough to be confusing, but it usually becomes clear with careful reading. And it doesn’t detract from the power of the storytelling.

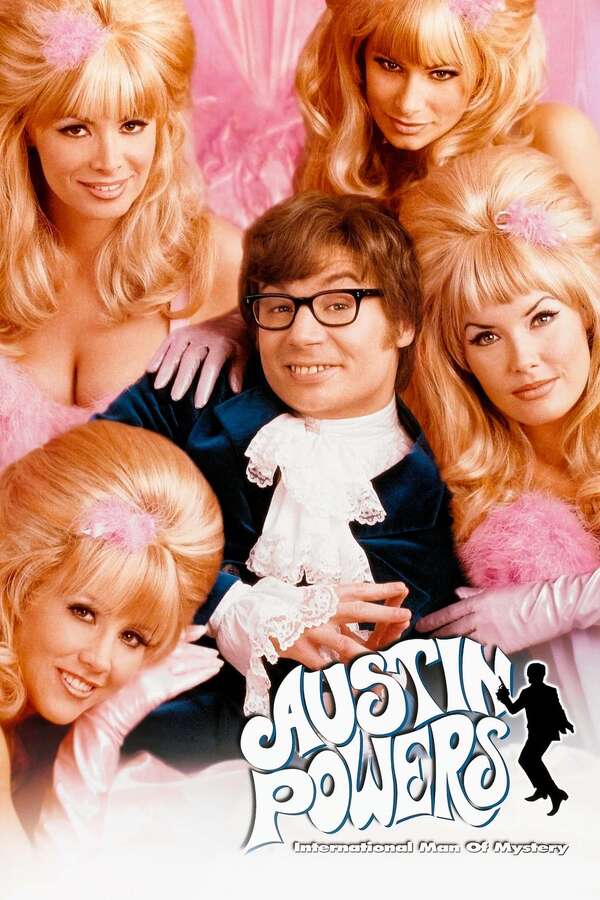

Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery, 1997 - ★★

I first heard of Mike Myers in 1985 or so, at the Edinburgh Fringe. Someone was giving out flyers for a comedy show (I know, at the Fringe, right?) If I remember correctly it was the opening night that evening, at St John’s on Prince’s Street.

A comedy duo called Mullarkey and Myers. We had probably heard of Neil Mullarkey, and there was an added incentive: a free bottle of Moosehead beer (owing to the Canadian nature of one of the performers) if you turned up with the flyer.

I don't remember anything about the show, but the name and its existence stuck. Years later came Shrek, in which the same Mike Myers did a Scottish accent for no very obvious reason. I assumed he had learned it that year in Edinburgh.

Somewhere along the way he made this, too. It's fine, but I already watched Our Man Flint this year, so…

In fact, if I’m not mistaken, the ringtone from Powers’s communication device is lifted from the presidential phone in Flint.

Films, Books, Blogging, and Giving Up

I’m realising I need to get back into the habit of putting things on the blog. More than film notes from Letterboxd and book notes. There won’t be another book note for a while because I’m reading Daniel Deronda by George Eliot. It’s 800 pages and I’m around the 200 mark.

I started reading something else after Eastercon — did I mention I went to Eastercon this year? Oh, yes, I did, but only briefly. it was in Birmingham, but not in the heart of the city with its many curry restaurants. It was at the Hilton Metropole, out near the airport and NEC.

Anyway, one of the guests of honour was Adrian Tchaikovsky, who I’ve been aware of but never read for lo! this several years. He seemed personable and interesting, and my friend Simon recommended his Children of Time. Turned out I already had that on my Kindle from some offer, so I started it.

And I stopped after about a third. I just wasn’t really enjoying it. The spider characters were kind of interesting, and the human ones much less so, and I just didn’t care that much about the plot.

Then I discovered that it’s the start of a series (or at least that it has sequels, which is not necessarily the same thing). That just put me off more, because if I’m not that interested in 400 pages or whatever, how much less interested am I going to be in three times that?

I’m not in the business of reading things because I “should”, either because they’re in some way classic, or just because I’ve started them. Sorry Adrian, sorry Simon.

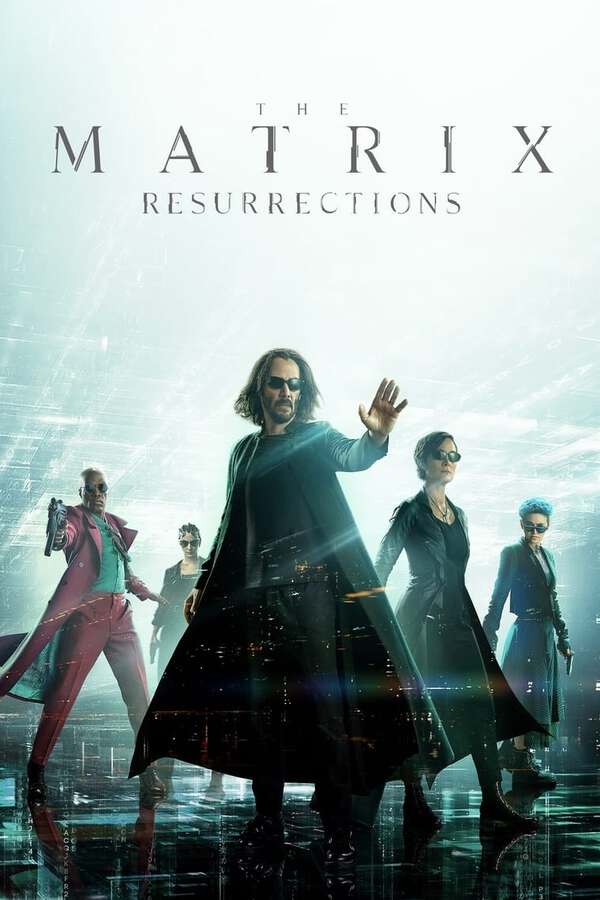

The Matrix Resurrections, 2021 - ★★★½

Forgot to log this when I watched it a month or so ago. I know I expressed high enthusiasm for this when it was announced in 2021 (that long ago?), but when it came out… actually, who knows?

Anyway, I finally watched it, and it's OK. It's fine, it was good to see some of the old gang back together. The references to the original and the expansion of the story were coherent (at least as coherent as the originals).

But it didn't wow me, which I suppose is kind of inevitable. The first film is one of my all-time favourites.

Far from essential.

Blue Jean, 2022 - ★★½

In the 1980s, under the fear of the Tory government's Clause 28, a teacher has to keep her sexuality hidden if she wants to keep her job. The arrival of a new student throws things up in the air.

It's pretty good, gives a real sense of how much fear the terrible legislation caused, while also showing how women can support each other — and sometimes fail to do so.