books

Transition by Iain Banks (Books 2019, 25)

This post was written in the new year, but the book was read in the old, and accordingly backdated.

This is a strong as it was ten years ago when I first read it, but still has the same narrative flaw. That’s not surprising, but the flaw in the universe-hopping detail is so jarring that I read it half-hoping to pick up on something that I had missed the last time.

It was not to be. Our heroes and villains still hop to uninhabited Earths, and yet find a body there to receive them.

And of course, the ethical question of possessing another human being remains barely addressed.

All that said, though, it’s still a great read.

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: The Tempest by Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill (Books 2019, 24)

The final volume of Moore’s League stories, and, he says, his final work in the comics medium. If so, it’s not a bad closer.

It occurs to me that a significant portion of his comics output has been built on the work of others. Nothing wrong with that. Indeed, it could be said to be true of all literature, maybe all art. Moore’s use is more frequent than most, though: The Watchmen characters based on those from old Charlton Comics; Marvelman/Miracleman a revival of Mick Anglo’s creation; Promethea digging into mythology and fiction, as I wrote very positively about last year; and so on.

In the League it’s at its most explicit. The main characters are Mina Murray from Dracula, Virginia Woolfe’s Orlando, and Alan Quatermain from H Rider Haggard’s novels (although he isn’t in this volume). Even the subtitle of this one is from Shakespeare.

There is, as I say, nothing wrong with any of that. It’s like sampling in music: it doesn’t matter that you’re using part of an earlier creation; what matters is what you do with it.

And what Moore and O’Neil do with everything here is pretty spectacular. I won’t go into any detail, but suffice it to say that pretty much all the threads from the earlier volumes are tied up, and everything is over at the end. Everything. Well, not everything everything. Not quite.

I wouldn’t start here, though: go back to the beginning if you want to read any of these. Read them all.

The Steep Approach to Garbadale, by Iain Banks (Books 2019, 23)

One interesting thing about this book that I don’t recall noticing when I read it twelve years ago is that the story itself is the titular approach. We don’t get to Garbadale House until about two-thirds of the way through, and then the rest of it is set there. With a few flashbacks and -forwards thrown in to both sections.

Banksie always plays with form and structure, and this is no exception. Not just the aforementioned directional flashes, but use of different viewpoint characters and tenses. Mostly it’s from the viewpoint of Alban McGill, one of the many members of the Wopuld family. Some scenes are from that of a cousin of his. There are even a couple of instances of promiscuous PoV, or “head-hopping,” where we get the thoughts of another character within the same scene.

Also some parts switch to present-tense, while most if it is past. There doesn’t seem to be any obvious function to those switches: it’s not like the tense reflects the timeline within the story. It seems arbitrary, almost random — though maybe I’m missing something there.

None of this harms the story, it’s just worth noting. The strangest of these devices is that there are three or four sections in first-person, from the PoV of a minor character. All the rest is third-person. That gives the impression that this character is more significant than he is. The text in those sections is also rendered with spelling mistakes and grocer’s apostrophes, as if it was the direct transcript of what this relatively poorly-educated character has scribbled down.

What’s the point of all that? I’m not sure. Just writerly games, maybe. I wonder if it suggests that Banks didn’t think the story itself was interesting enough to sustain the narrative, which might be a valid criticism. A well-off family with a secret at its heart has to decide whether to sell its business. The secret comes out, but it doesn’t make much difference. It would be significant to the characters affected, but we hardly see them after the reveal.

Endearing characters, though, and even on a second read (I didn’t recall the secret), it keeps the pages turning.

As I said twelve years ago, “In a book like this, the pleasure is in the journey more than the destination.”

The Book of Dust vol 2: The Secret Commonwealth by Philip Pullman (Books 2019, 22)

You shouldn’t read this book.

Yet.

I broke a personal rule, that goes back to 1982: Never start reading a fantasy series if the final volume hasn’t been published.1 1982 was the year I was reading Stephen Donaldson’s The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant. The fifth volume (or second volume of the second series) was out, but the sixth and final wasn’t.2 I waited on tenterhooks.3 Eventually the hardback came out, but it was much too expensive for a poor student like me. Luckily, not for another poor student on my corridor, who lent it to me.

I learnt my lesson, back then. More or less: I was reading Harry Potter while it was still being written. But this is one of the main reasons why I never started A Game of Thrones, for example.

But here we are. Two-thirds of the way in to a compelling, thrilling story… actually that’s not quite right, what with the first volume being prequel. More like halfway through a very long story, and all I can say is… not very much without going into massive spoilers.

I like that Lyra is using Silvertongue as her surname: a name she was given, that she earned. There are aspects of the world, of Lyra’s relationship to it, that are surprising, given what she went through in His Dark Materials. But then, it is eight years later, and she has grown up a lot.

Politics and events in the world of the Magisterium sometimes parallel those in our world.

It’s a lot darker and more adult-themed than the original trilogy. I don’t know if the whole will end up being as legendary or as moving as the original, of course, but at this point, balanced on the fulcrum of change, I like it almost as much.

I lied at the the start: you should read this book. But be prepared for the fact that we might have to wait two years for the conclusion.

- At a pinch, if the author hasn’t finished writing it. ↩

- White Gold Wielder was released in 1983, I see. And I gather that he’s since written a third trilogy, but… nah. ↩

- Well, maybe about five or sixterhooks. ↩

Kieron's Comic, Brontë's Book

One of the comics I read is Kieron Gillen’s1 Die, which is about a group of people who get sucked into a fantasy world. The world is based on a role-playing game — or at least, it seems to be at first. The other night I started the latest issue, 9. Unexpectedly — but not surprisingly — Charlotte Brontë turned up as a character (or maybe not, but let’s run with it). The story was about how she and her siblings had created complex fantasy worlds in part as stories for their toy soldiers. And maybe the world of Die is based in part on those.

Imagine my surprise, then, when I woke the next day to hear on the radio news that a tiny book — “no bigger than a matchbox” — written by Charlotte, was being auctioned in France. It is filled with stories of the fantasy worlds created by her and her siblings.

The book has been bought by the Brontë Society. It will be kept in the Brontë Parsonage Museum, where it was created.

Two completely unrelated events, of course, but interesting how things collide.

- He seems not to have website of his own, bizarrely, but he has a Tumblr, and a newsletter. ↩

Watchmen by Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons (Books 2019, 21)

I like to reread this from time to time, and right now I’m considering watching the TV version that’s currently on. It’s HBO, which means Sky over here, which would traditionally have ruled it out on ethical grounds. But times and corporate ownerships have changed. The Murdochs no longer own Sky TV, so I can let myself watch it.

But then we have the other ethical question, about Watchmen in particular. Which is to say, since Alan Moore feels that he was cheated by DC over the ownership of the creative work, and repudiates all derivative works, shouldn’t we avoid them too? I saw the movie version, but I didn’t get the Before Watchmen spin-offs.

Well, it’s been a long time; Moore and Gibbons must have known what they were signing up for, even if things didn’t go quite as they expected. I recall seeing Moore at a convention in Glasgow in 1985 or 86, where he said, “DC are utter vermin.” Yet he went on to work with them often after that.

Plus, I’m already reading Doomsday Clock, which brings the Watchmen universe into the DC multiverse, so personally, that ship has sailed.

How does the story stand up today? It’s still excellent, I would say. With the obvious weakness of the ending. Though thinking about that, what’s weak is how preposterous Veidt’s plan is. Accepting that, that part of the story is well executed.

It’s still one of my favourite comics.

Northern Lights, The Subtle Knife and The Amber Spyglass by Philip Pullman (Books 2019, 18, 19 & 20)

His Dark Materials, as I said.

Holy hell, this trilogy is good! I think I’d forgotten just how good it is.

In the first book we meet Lyra, a wild orphan who lives in fabled Jordan College in a parallel Oxford. Plots and adventures quickly ensue.

The second volume starts with Will, a boy who lives in our world, and who has to run from his home because he has killed someone. How will his story connect to Lyra’s?

And the third builds on everything that has gone before, and a whole lot more.

There are armoured bears, angels, daemons, airships, witches, harpies, the dead, and much else. The fate of worlds hangs in the balance.

If you haven’t read it, you should. You could start watching the TV series instead, but I expect there’ll be a long wait between the seasons, and the books are right there.

Of course, I’m going to find myself in a similar position with the sequels. It was eighteen months ago that I read part 1, so presumably we won’t get the conclusion till some time in 2021.

I like what they’re doing with the TV series so far. Enough changes to keep it interesting, not enough to spoil it.

On Pausing Stories

Almost exactly a year ago I started reading a novel, then put it on hold. This year I’ve done the same, for different reasons.

I started The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet by Becky Chambers in October of last year. I quickly put it aside as November approached. I realised that it — or at least its start — was much too similar to the novel that I planned to start for NaNoWriMo.

I haven’t got back to it yet.

This year it was the new Philip Pullman, The Book of Dust vol 2: The Secret Commonwealth

Now, you’ll recall that I said I might do this after I read the first of the new trilogy. Other things got in the way of that, though.

So I read a chapter or two of the new one, and realised I needed to refresh my memories. There’s a whole thing that we learn about at once that I don’t remember. Or at least don’t remember how it happened.

There’s also a TV series coming. I was aware it was in development, but not of how soon it was going to be. Turns out it’ll be on in a week or two.

So now I’m worried that watching it is going to be a bit like the recent Good Omens series was for me; really well done, I appreciated it… but I had re-read the book too soon before watching it, meaning it was all just a bit too recent in my memory for maximum enjoyment. But we’ll cross that ice bridge to another world when we come it it. The trailers look great, anyway.

The difference with this year’s pause will be that, while I will get back to the Chambers eventually, I’m obviously not in any hurry to do so. Whereas I fully expect to restart The Secret Commonwealth as soon as I’ve recovered from the ending of The Amber Spyglass. Which I’ll probably be starting quite soon.

Hannah Green and Her Unfeasibly Mundane Existence by Michael Marshall Smith (Books 2019, 17)

No, it’s me, not London Below: this has also faded quickly from my mind, despite the fact that I love MMS, and I really enjoyed this as I read it.

Still, it’s very good. Hannah is an ordinary girl living in present-day California with her dad and (maybe) mum (sorry, mom).

Until the devil turns up, and her grandfather turns out to be his engineer. And he knew Bach.

Inevitably, the world needs to be saved.

Neverwhere by Neil Gaiman (Books 2019, 16)

While I was reading this I thought it was probably my favourite of Gaiman’s prose works. And I thoroughly enjoyed it. But just a couple of weeks later, as I write, it’s already fading from my memory.

Maybe that’s just me, or maybe it’s London Below.

Either way, well worth a read.

The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood (Books 2019, 15)

It’s to my shame that I hadn’t read this classic of modern literature before now. And it turns out, now that I have, that it’s really good. Surprise, surprise. I don’t really care for dystopias, as I’ve said before. Interesting that the book I linked to there had just won the Clarke, and the one we’re discussing was the inaugural winner of that award.

For the first few chapters I was distracted by wondering how this situation, this state, could have come to be. Strangely what I found difficult to cope with was not the restrictions, the rolling back of rights — they are horrific, but I could and can easily imagine an America (or, hell, maybe even a Britain) that could enact those laws.

No, what I found hardest to believe in was the dress codes. The way not just the Handmaids, but the marthas (domestic servants), econowives (lower-class, probably infertile women, assigned to lower-class men) and even Wives (the wives of the ruling-class men) all dress in the standard costume of their class.

Somehow I feel — or at least felt — that it would be harder to get everyone to dress the same way than to obey laws that restrict more important freedoms.

As the chapters went on, those concerns evaporated. The telling of the backstory through Offred’s reminiscences outlines a convincing route from 80s America to Gilead. Though a lot more could be told: it is only an outline. Still, it’s enough.

These days, with actual nazis poisoning our political discourse, and attempts to roll back reproductive rights even in France, it sometimes feels — as Atwood no doubt intended — that Gilead is not so much a fable as a warning.

The Seventh Function of Language, by Laurent Binet, Translated by Sam Taylor (Books 2019, 14)

I need to start making notes about where I hear about books. This hasn’t been on my Kindle for long, but I have no idea what prompted me to buy it.

I’m glad I did, though. This is great. It’s set in 1980, and Roland Barthes, the philosopher and semiologist (semiotician?) gets knocked down I the street by a laundry van. He dies later in hospital.

That much is true. But Binet uses it as the jumping-off point for a mystery caper of sorts, in various picturesque cities in Europe (and a brief dip into the US). Because Barthes was believed to have been carrying a paper detailing the titular function.

Along the way we learn things about semiotics and linguistics, aided by the police officer who is investigating the case

It’s a strange one, but pretty good.

The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson (Books 2019, 13)

A genuinely chilling, even scary, ghost story, is not something you read that often. Or I don’t, these days, at least.

Combine that with compelling characters, comedy, and tragedy, and you’ve got kind of a small masterpiece.

I only say “small” because it’s quite short. I only know Jackson from a film version of “The Lottery” that they used to show us in school. I’m not sure why they showed us it, exactly, because we didn’t study it in English, and as far as I recall we didn’t discuss it. I think maybe it was a sort of treat, and the school only had a few films, that it showed repeatedly. These were actual films, I should add. Played on a projector, watched on a screen.

Anyway Jackson’s story always stuck with me, and now this one joins it.

The 392 by Ashley Hickson-Lovence (Books 2019, 12)

We went to WOMAD a couple of weekends ago, and in the literary tent we caught the end of a reading from, and an interview with, this young Hackney writer. It was an interesting talk and the book sounded compelling, so we bought a copy (and got it signed).

It’s set over 36 minutes on the inaugural journey of a new (nonexistent) London bus route, from Hoxton to Highbury. Told as the thoughts and conversations of various passengers (and the driver).

If you’re familiar with the area and the local slang (which may in fact be national or global slang in places), it’s particularly enjoyable. But the themes are universal, so don’t suppose it’s only for Hackney & Islington folk.

I have my problems with the ending, but it’s well worth checking out (and it’s very short, and in bite-sized pieces, if you’re looking for something easy).

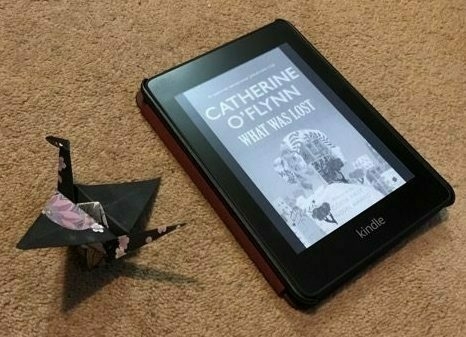

What Was Lost by Catherine O’Flynn (Books 2019, 11)

This was recommended to me by an Open University tutor when I was doing the creative writing course a few years back. Which experience, I note, I barely wrote about here. I have a Diploma in Creative Writing, don’t you know?

Anyway, there was an exercise which included writing a plan for the next major piece we were going to write. I wanted to write something that was set in an exotic city, and I mentioned in my plan that I wanted the city to be a character in the story. I was thinking maybe of something like China Miéville’s Bas-Lag.

My tutor suggested that the shopping centre in this book might be a similar kind of thing. Which turns out not really to be accurate. It’s set largely in and around the mall, and some people say they have a sense of it watching them, but nothing is ever made of that.

It’s strange, in that it starts off apparently being a kids’ book, or at least YA; but after the first part it takes a turn, into something else entirely.

It’s not bad, but I wouldn’t particularly recommend it.

Milkman by Anna Burns (Books 2019, 10)

This is not mainly a book about The Troubles; nor about religion or politics, though it is about all of those. It's a book, above all, about gossip and rumour and silence, and the harm that those can do to a person, to a society.

The unique approach — no-one is named, almost no proper names appear — I found quite endearing. And far from obfuscating things, it many ways it makes the story easier to follow. Instead of having to remember whether Mary, Margaret or Roisin is the oldest sister, it's “first sister.” “Oldest friend;” “maybe-boyfriend.” Honestly, all books should be like this. Relationships are important, after all.

Though you can also see it as a sly reference to the common complaint about living in small communities, that you're always someone's daughter, someone's brother — never yourself.

Anyway, Booker Prize winner, and all. Dead good.

Touch by Claire North (Books 2019, 8)

I enjoyed North's previous novel , with some reservations. This one was similar. I read it in a day — it's quite the page-turner — and it has a compelling plot trigger.

The first-person narrator is an entity who can jump into any human body from its current host, just by making skin-to-skin contact — the "touch" of the title. Male or female, young or old, it doesn't matter. The host doesn't know anything about it while they are possessed, and is left unharmed — unless, of course, something happens to their body while the possessor is in control.

Sounds pretty gruesome like that, so it's impressive that our sympathies are with the narrator throughout.

Good story, slightly flat ending. Hey-ho.

In Dreams: A Unified Interpretation of Twin Peaks & Other Selected Works of David Lynch, by H Perry Horton (Books 2019, 7)

This is an incredible piece of work, about an incredible body of work.

I don’t recall how I heard about it. I think I saw a tweet, or something, thought it looked interesting, and instantly bought it because it was only a few quid on Kindle. It’s a huge book which tries — successfully, in my mind — to explain how the bulk of David Lynch’s creative works can be considered part of a single story, which Horton refers to as The Dream.

Now obviously Twin Peaks, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, and Twin Peaks: The Return are all part of the same story. As are the various spinoff books: Jennifer Lynch’s The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer, and Scott Frost’s The Autobiography of FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper: My Life, My Tapes, from back around the time of the original broadcast; and Mark Frost’s more recent The Secret History of Twin Peaks and Twin Peaks: The Final Dossier, which I’ve written about here.

But Horton argues that the whole story gets kicked off in Eraserhead, and that Blue Velvet, Lost Highway, Mulholland Dr and Inland Empire are side stories related to the main branch. The overall story being about an eternal being, The Dreamer, who dreams reality into existence, and also creates another being, known as Jowday, or Judy, who becomes his adversary. BOB, the possessing spirit of the original Twin Peaks, is a creation of this entity, and the Black and White Lodges are the vanguards in the battle between the two beings.

Sure, on one level it’s just good vs evil, heaven & hell — “just,” I say, as if that wasn’t enough. But the sheer scope of it is astonishing. The eighteen hours of The Return has been hailed as an incredible masterpiece of visual storytelling. But when you include all that I’ve listed above, and three of Lynch’s paintings to boot — it must be one of the greatest — in terms of size, at least — creative works by a single visionary. True, it’s far from being by a single creator, but the vision behind it is solely or primarily Lynch’s, or that of Lynch and Mark Frost.

And even if the connections to the other films are just in Horton’s head (and, to be fair, those of others whose work he acknowledges): the obviously-connected stuff is still amazing, and the current work, Horton’s book that I’m writing about, is something a of a creative triumph itself.

One that is slightly marred by its self-published nature and obvious lack of an editor — there are a lot of typos — but a hugely impressive one nonetheless.

Though obviously it’s only for the very serious Twin Peaks fan.

Good Omens by Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman (Books 2019, 6)

A re-read of Pratchett & Gaiman’s comedy-horror masterpiece, prior to the forthcoming TV series.

I remembered little, and/but enjoyed it immensely. Probably more this time than whenever it was I last read it. You don’t have to have read The Omen to enjoy this, just in case you thought that.

Oh, turns out it was in 2007: the twelfth book I read that year. I’m starting to repeat myself.