books

📚 Books 2026, 4: Caledonian Road, by Andrew O'Hagan

I really enjoyed this. It’s set in London (mostly), in a later year of the pandemic (2022, probably), and across just over a whole year. The characters are people from the upper-middle to upper classes, and some of the lowest classes in society, including criminals and illegally-trafficked people who have to work for them.

Some of the blurbiness on the cover describes it as a ‘state of the nation’ novel. It doesn’t quite seem like that for me (though I don’t know if I could give you an example of one that is), not least because the main characters exist at a fairly rarified level of society. They are things like academics, authors, journalists, MPs and lords. Or else they’re would-be drill rappers in street gangs. There’s nobody who’s just normal; whatever that means.

There are so many characters that O’Hagan provides a list of them, a dramatis personae, which I approve of.

Anyway, it’s very good, and I read it much faster than I expected to, which is usually a good sign.

📚 Books 2026, 3: How to Seal Your Own Fate, by Kristen Perrin

As I said a couple of days ago, the second Castle Knoll Files book isn’t quite as good as the first. It’s a fun enough read, but it feels slight as a work of detective fiction, compared to, say, Christie or Rowling, the main crime writers I’ve read recently.

And there are some incongruities. The writer is American, though she has lived in the UK for years, and it shows. Especially in the parts that are written as being a diary from 1967 (the main narrative is present day). Modern terms are used in ways that they wouldn’t have been back then. No examples come to mind right now, but I might update this if they do.

And there are occasions of dialogue that reads more like exposition. People just don’t talk like that.

Apart from those relatively minor points, I enjoyed it a lot, and will doubtless get the third book, which is due out in April. I wonder both for how long Perrin will be able to keep coming up with titles that match the style; and for how long our intrepid investigator, Annie Adams, will be able to find cold cases in great-aunt’s notes.

📚 Emily Tesh wrote the best SF book of the last couple of years (not just my opinion, it won the Hugo). Now The Incandescent is an incredible fantasy book, a magic-school story for adults.

She’s so good she almost scares me. Yet she just seemed to appear out of nowhere.

📚 Books 2026, 1: The Cold Six Thousand, by James Ellroy

The first book of this year, or the last of last? I started reading James Ellroy’s The Cold Six Thousand a couple of weeks before Christmas, set it aside for some Christmas books, and then went back to it.

I started reading it once before, years ago, and didn’t get far. And I think that’s because of its very strange style. Ellroy uses a chopped-up style of extremely short sentences, much repetition of names, and almost no use of pronouns. For example:

The witnesses were antsy. The witnesses wore name tags. The witnesses perched on one bench.

Or:

Wayne ducked by. Wayne passed a break room. Wayne heard a TV blare.

And that kind of thing is repeated across 600+ pages. It can be hard work at times. The only relief comes in some chapters that purport to be transcripts of phone conversations recorded by the FBI.

We are in the real world here, in the sixties. Right at the start, JFK is assassinated. The three viewpoint characters are all dodgy members of various law-enforcement agencies (Las Vegas police, FBI, CIA) and are all connected to the conspiracy behind that event (spoiler, it was the mob, but certain others, like J Edgar Hoover, weren’t too bothered and/or were sort of involved).

The story carries on through the sixties up to the other to big political assassinations, of Martin Luther King and RFK. And guess what? Our antiheroes — or some of them, at least — are involved in those too.

It’s a novel of the sixties, then, about conspiracies and secrets. Not unlike my beloved Illuminatus! trilogy. So why don’t I love it, then? Mainly, I think, it’s that stylistic choice. I don’t see the point of it, and I found it quite annoying, until eventually it became almost comical. And I did enjoy the book (otherwise I would have stopped reading, what with life being too short to read a book you’re not enjoying). Just not as much as might be expected from the setting.

There’s also this: I learned when I was around half way through that this is actually the middle volume of a trilogy. I’ve noted before, though perhaps only in footnote, that publishers seem to hate putting numbers on books1, or otherwise letting the reader know important details like that. And it doesn’t matter that much here. It works OK as a standalone novel. But I realise now, part of the strangeness at the start may have been a kind of sense that we were expected to know the characters to some degree. I wrote about something like this fifteen(!) years ago, and the sensation I had this time (I now realise) was similar.

Lastly, it’s a very brutal book. There are many acts of extreme violence, described in casual, if not loving, detail. And the casual racism of the language will probably upset some people even more than the violence.

So I’m glad I’ve finally read it, but I don’t see me searching out the other parts of the trilogy.

-

‘The Cold Six Thousand? I haven’t read volumes one to 5999 yet!’ ↩︎

📚 Books 2026, 1: The Cold Six Thousand, by James Ellroy

The first book of this year, or the last of last? I started reading James Ellroy’s The Cold Six Thousand a couple of weeks before Christmas, set it aside for some Christmas books, and then went back to it.

I started reading it once before, years ago, and didn’t get far. And I think that’s because of its very strange style. Ellroy uses a chopped-up style of extremely short sentences, much repetition of names, and almost no use of pronouns. For example:

The witnesses were antsy. The witnesses wore name tags. The witnesses perched on one bench.

Or:

Wayne ducked by. Wayne passed a break room. Wayne heard a TV blare.

And that kind of thing is repeated across 600+ pages. It can be hard work at times. The only relief comes in some chapters that purport to be transcripts of phone conversations recorded by the FBI.

We are in the real world here, in the sixties. Right at the start, JFK is assassinated. The three viewpoint characters are all dodgy members of various law-enforcement agencies (Las Vegas police, FBI, CIA) and are all connected to the conspiracy behind that event (spoiler, it was the mob, but certain others, like J Edgar Hoover, weren’t too bothered and/or were sort of involved).

The story carries on through the sixties up to the other to big political assassinations, of Martin Luther King and RFK. And guess what? Our antiheroes — or some of them, at least — are involved in those too.

It’s a novel of the sixties, then, about conspiracies and secrets. Not unlike my beloved Illuminatus! trilogy. So why don’t I love it, then? Mainly, I think, it’s that stylistic choice. I don’t see the point of it, and I found it quite annoying, until eventually it became almost comical. And I did enjoy the book (otherwise I would have stopped reading, what with life being too short to read a book you’re not enjoying). Just not as much as might be expected from the setting.

There’s also this: I learned when I was around half way through that this is actually the middle volume of a trilogy. I’ve noted before, though perhaps only in footnote, that publishers seem to hate putting numbers on books1, or otherwise letting the reader know important details like that. And it doesn’t matter that much here. It works OK as a standalone novel. But I realise now, part of the strangeness at the start may have been a kind of sense that we were expected to know the characters to some degree. I wrote about something like this fifteen(!) years ago, and the sensation I had this time (I now realise) was similar.

Lastly, it’s a very brutal book. There are many acts of extreme violence, described in casual, if not loving, detail. And the casual racism of the language will probably upset some people even more than the violence.

So I’m glad I’ve finally read it, but I don’t see me searching out the other parts of the trilogy.

-

‘The Cold Six Thousand? I haven’t read volumes one to 5999 yet!’ ↩︎

📗 Books 2025, 30: Slow Horses, by Mick Herron

It’s interesting to discover that this is a great read even though I’ve seen the TV series. An interesting parallel with early last year, or rather last thing in 2024, when I read Conclave, not long after seeing the film.

If you’re unfamiliar with Mick Herron’s ‘Slough House’ stories, the series is up to four seasons now — or is it five? — on Apple TV. And it’s really good. This is the book that started it all, and it’s excellent. A group of misfit MI5 spies, each of which has been shunted aside from the main track because of some mishap or fuckup.

📗 Books 2025, 28: The Book of Dust vol 3: The Rose Field, by Philip Pullman

I said I wouldn’t say much about the previous book till I’d read this one, since they’re really all of a piece, a single story spread across the two. And now here we are. Oh, and there are spoilers below.

Trouble is… it doesn’t feel like we’re quite finished.

To summarise: I mostly enjoyed the story very much. There were points where I was just wanting it to end, but in the sense of wanting to find out what happened, not of wanting it to be over. Lyra and Pantalaimon can separate, since their adventures in the original trilogy (something I had completely forgotten when I first read volume 2, which is part of the reason I reread the originals back then). And they’re not getting on with each other at the start of volume 2. In fact, Pantalaimon leaves Lyra, goes off on his own, to find, he says, her imagination.

Which sets up the main driver for the two books. Or one of the main drivers. Because there’s a lot going on beyond Lyra and Pan’s life. Specifically, the Magisterium is up to its old shenanigans and a whole lot of new ones, and there’s a war brewing. Or being brewed. But it’s not clear to the ordinary people of Brytain (as they spell it over in Lyra’s world) who or what the war is against.

Lyra and Pan travel east by different routes. Along the way they meet gryphons and witches and humans and, of course, daemons. Some of the humans seem to barely believe their daemons exist, which is odd.

And there are still windows between the worlds — presumably opened by some past bearer of the Subtle Knife — and the Magisterium is trying to destroy them with explosives and some success. Because, they believe (or their new pope-like leader claims to know) the windows let evil into the world.

Or something like that. The ravings of religious nutters doesn’t make much sense. This new pope-like guy is, by coincidence, Mrs Coulter’s brother. That is, he’s Lyra’s uncle. We assume, therefore, they’ll meet towards the end.

Reader, they do not meet. And that’s only the least of what feel like a great deal of loose ends. In fact there are so many points of interest that we might have expected to be resolved that are not, that this feels like the middle volume of a trilogy, not the final one. Which makes sense, considering the first volume of this trilogy was a prequel to the originals, while the second two comprise a sequel. It feels like Pullman wanted to, or should have, written a full sequel trilogy.

I mean, I don’t mind a few things not being resolved. Stories never end, really, they just stop. But there’s just so much here feeling like untold stories. Maybe he’ll release a series of standalone shorts, as he has before with things like ‘Lyra’s Oxford’. Maybe he really has another volume up his sleeve, but if it takes another six years to write it… well, he’s not getting any younger.

Where we’re left is not terrible. Lyra and Pan are back together and reconciled, and the immediate active dangers are stopped. But they’re in another world that doesn’t seem great, and if they go back to their own, they’re a wanted terrorist, thanks to their uncle’s work!

I express the previous paragraph in the way I did to make a point that occurred to me about Lyra’s world. All humans have daemons, which are part of themselves. An externalised part of their personality or psyche. The human and daemon talk to each other, and will talk about themselves doing things, saying, ‘When we sneaked into the catacombs…’ and so on. We. The thing Pullman missed, I think (and I’m sure his Exeter College predecessor, JRR Tolkien, would not have missed) is: language would be different. Ordinary, everyday language. There would hardly be a personal singular pronoun. Or it would still exist, but be used in a different way.

There would probably be different forms of the first-person plural, too. A ‘we’ that means one human and their daemon referring to themselves. And another form of ‘we’ that means a group of people (and their daemons) together.

Anyway. Just a thought about language. And I want more, Mr Pullman, but I don’t expect it. Still a great story, just not quite the ending I was hoping for.

📗 Books 2025, 27: The Book of Dust vol 2: The Secret Commonwealth, by Philip Pullman

I started to dip into the new one, but as I said I might, I decided it had been too long. I went back and reread this one. And I’m very glad I did. I had forgotten many of the details, remembering only a few high and low points.

I really enjoyed it, and won’t have much to say about it till I’ve finished the new one, which I’m already well into, you won’t be surprised to hear.

There is the suggestion that some gates between the worlds are still open. Are any of them to our (Will’s) world? And would we want Lyra and Will to be reunited, if that were possible? It would undermine the ending of the original trilogy, but if done right…

That said, I don’t think that’s where it’s going to go. Just the idle musings of a shipper.

📗 Books 2025, 26: Matrix, by Lauren Groff

A book about nuns in the 12th century? Why not? Austin Kleon rates it, which is how I came to it.

About one nun, more accurately, a real historical figure, who may or may not actually have been a nun at all: Marie de France. She was definitely a poet, though.

None of that really matters, though. The book isn’t a biography, it’s fiction. A novel based loosely on a historical figure about whom not much is known. She’s descended from a fairy, or said to be in the story. She has visions of (or from) the Virgin Mary. She saves an abbey full of nuns from starvation, and turns it into a power in the land.

It’s very good. In my ongoing, unstructured notes on how writers present speech, and such: there is no direct speech at all in this. Or there is at times, but it’s not punctuated as such. I would have expected to find that annoying, but actually I hardly noticed it.

Groff is an excellent writer, I would have to say. I’ll be keeping an eye out for more by her.

📗 Books2025, 25: Summerland, by Hannu Rajaniemi

I enjoyed this, but it hasn’t really stuck in my mind. By which I mean, I finished it a few weeks ago, and don’t really recall much of it now. I’ve read two of Hannu’s hard-SF trilogy, but never got to the third, despite what I predicted back then. They were hard work, as I recall, which is probably why I never got to the third.

This one, which was recommended by Warren Ellis is much more approachable. It’s 1938 and the afterlife has not only been discovered, living humans can communicate with the souls in it. And the intelligence services of the the Great Powers are making use of it to extend the reach of their empires.

It’s good, but thinking about it now, one idea that’s mentioned and doesn’t really get explored is this. People no longer fear death. When you know there’s an afterlife — and especially when your one of the privileged ones with a ‘Ticket’, that means your soul will persist in ‘Summerland’ and not dissipate — then there’s nothing really to fear.

But it’s a spy story, so the focus is on the plot, as it should be, and it’s a good one. Thought it maybe slightly runs out of steam at the end. Worth checking out, though.

‘[W]e might have to wait two years for the conclusion’ I wrote almost six years ago.

The conclusion of The Book of Dust arrived the other day. I haven’t started it yet, and now I’m thinking I might go back and reread the previous one first.

📗 Books 2025, 24: Under the Glacier, by Halldór Laxness, Translated by Magnus Magnusson

This is a very odd little book. Laxness won the Nobel for Literature back in the fifties, but I had never heard of him before I read Jack Deighton’s review of it earlier this year. This is often the way with Nobel laureates, or so it seems to me. The committee members know of many more writers than you or I.

In her introduction, Susan Sontag includes science fiction in the group of labels of ‘outlier status’ which apply to this novel. Only, I would say, if some characters believing they are ‘in communion with the galaxies’ makes it so. Yet it somehow has something of the feel of SF. Maybe because our unnamed narrator is exploring a landscape in which he is lost and confused.

It’s the psychological landscape of a small community who live by the titular glacier, though. And that glacier — Snæfells — is the same one Jules Verne’s characters start their Journey to the Centre of the Earth. Which gives it a tentative connection to one of our ur-texts. But nothing explicitly fantastical happens. Unless it does. Resurrection? Maybe. Somebody disappearing mysteriously? Possibly.

We, the reader, are as lost and confused by the behaviours of the characters as is the narrator, who has been sent by the bishop of Iceland to find out what has been going on in the distant parish.

It muses on a lot of ideas (SF is ’the literature of ideas’, of course, so there’s that), but has no plot as such. It’s intriguing, though, and well worth a read.

📗 Books 2025, 23: How to Solve Your Own Murder, by Kristen Perrin

Most sites describe How to Solve Your Own Murder as ‘cosy crime’, which I suppose it is. It has a first-person protagonist, so the reader doesn’t think there’s much chance she’ll die. She does find herself in some danger, though, and hell, she might not inherit her great aunt’s fortune, if she doesn’t solve the mystery of her murder.

The great aunt’s murder, that is. Our heroine has never met the great aunt at the start, and never does, because she’s murdered right away. But we know from a prologue that the great aunt always expected to be murdered. A medium told her so — or at least implied as much — when she was 16. It became the defining fact of her life, which is quite sad.

The great aunt is a secondary first-person narrator, by way of her diaries. So we get alternating chapters of the past and present. It’s a good read.

I did something unusual for me at the end: I read the few pages fom the sequel that are included at the back. Usually I skip that kind of thing. Especially when it’s not from a sequel, but from another book entirely. Not this time, though, and I’ll be seeking out How to Seal Your Own Fate (‘Book two in The Castle Knoll Files’) at some point.

📗 Books 2025, 22: Orbital, by Samantha Harvey

A Booker winner, no less. And a science-fiction novel, too. Well, of sorts. It’s set in space, but very much the non-fictional, real space of the International Space Station, and the present day. And nothing weird or fantastic (in the fantastika sense) happens.

Yet it is set slightly into the future. On the day it takes place — the whole story happens across a single day, sixteen orbits of the space station — a new mission to the moon is launched. A crew of four, scheduled to land on the moon a few days later. Is that enough to make it SF? Kind of. If it were up for SF awards, which I’m sure it must have been, few would quibble.

But none of that matters compared to how gorgeous the prose is. This is a very writerly novel. The language is lovely, almost poetic in places; yet with a lot of lists, oddly, both from the author and from at least one of her characters.

I was, however, mildly annoyed at times, in two aspects of my being. The physics graduate disagreed with some word choices. Right in the opening line, for example, a space station in orbit is described as ‘rotating’ round the Earth. While that’s not exactly wrong, it’s not how we’d usually phrase it. Orbiting or circling, we’d say. It might be rotating too, but that would be around its own axis. A tiny thing, though.

Then the writer and user of English was mildly disturbed by how the small amount of dialogue was presented: no quote marks. That’s not uncommon nowadays, but it can be distracting, and what purpose does it serve?

It’s a delightful work. There isn’t much plot, but there are fragments of all the six crew members’ stories. We see them at work, performing experiments and maintaining the station; watching a typhoon building on Earth and worrying about the people in its path; and musing about and remembering their lives and families back home.

It’s incredibly skillful to conjure so much from so little text — it’s unusually short for a modern novel. A worthy winner, and very highly recommended.

📗 Books 2025, 21: The Book of Daniel, by EL Doctorow

It’s a strange thing, or so it seems to me, to deal with a political event of your own lifetime, by writing a fictional version of a life. And not of one of the protagonists, but of an imaginary version of one of their children. Yet this is what we have here, and it’s on the whole successful.

Doctorow takes the story of the Rosenbergs, who were accused of conspiracy to commit espionage against the USA, convicted, and executed in 1953. Changing their name to Isaacson, he tells the story of their son, Daniel, along with his younger sister, Susan. In reality the Rosenbergs had two boys, but their ages were similar, and some of what happened to them after their parents’ arrest, according to Wikipedia, is similar to the experiences of Daniel and Susan.

As a novel it’s extremely well written, both readable and literary. It uses a number of devices — I might call them gimmicks, if that didn’t seem too dismissive, but I’m not sure I understand the reason for them. It switches frequently between Daniel’s first person and third — sometimes within the same sentence —, and also jumps around in time. One section is told from the point of view of the father and mother, which makes sense, as it’s when they are in prison and on trial, where Daniel would have no access to them.

The whole thing is presented as the thesis (or part of it) that Daniel is writing for his PhD, so there are several levels of meta involved. The main problem I had with it was the adult Daniel is at times a thoroughly objectionable character. There are a couple of early scenes where he sexually humiliates his young wife that nearly made me throw the book across the room.

Protagonists don’t have to be pleasant characters, of course, but this seemed prurient to me. I suppose we’re meant to understand he’s been damaged, if not abused. by his experiences, and goes on to abuse in turn. But I’m not sure the two sides tie up that well. The scenes of the young kids trying to make their way after their parents are gone, running away from an awful children’s home and returning to their now-empty house, are very moving.

Susan is in a mental institution at the start, and apparently dies there. Her story is the one that’s missing from this, in fact. We learn about her as a kid, certainly, and there are some interactions with Daniel when they’re older, then they’re estranged for a while. Then he visits her at the institution and she dies offstage. It feels like a gap, but again, maybe that’s how life feels sometimes.

As I say, it’s an unusual choice. Doctorow could have written a story about children torn from their parents and all that implies, without making it so closely tied to real events. Or he could have written a biography of the Rosenbergs. The latter would be a different kind of thing, though, and probably have a different readership. You’d only read such a biography if you were specifically interested in the case or the people, while you can read this as a novel without even knowing it’s inspired by real events. And maybe that’s the reason for using the events as the seed.

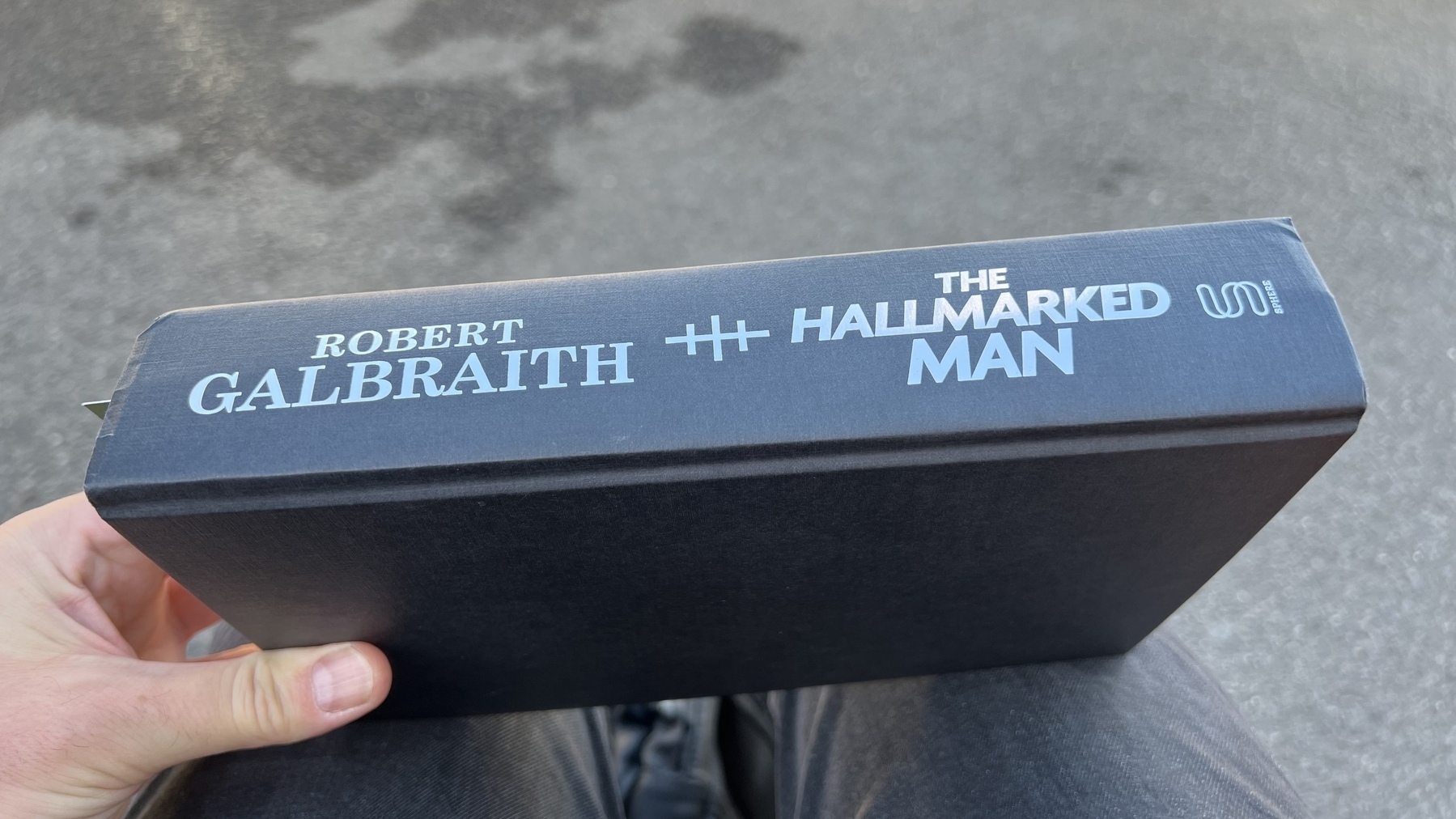

📗 Books 2025, 20: The Hallmarked Man, by Robert Galbraith

The mighty JK Rowling’s latest reaches us, at long last. After the bombshell ending of The Running Grave two years ago, we have the next installment in Strike and Robin’s story. (That should really be ‘Strike and Ellacott’s’, or ‘Cormoran and Robin’s’, but sometimes you’ve got to write things in the way that feels right).

The case is way complex. I’m not sure I followed all the twists, or even quite had all the characters figured out — especially actual and possible victims, even more than culprits. That’s partly because of the speed I read it at, and the late nights my reading caused.

Anyway, I’ll not say too much more because of spoilers, but I think The Ink-Black Heart is still my favourite.

180 pages in, and it’s only publication day. My local bookshop got my preorder in early and let me collect it.

Took the dustjacket off because it’s fiddly to hold.

📗 Books 2025, 19: In Ascension, by Martin MacInnes

It’s unusual to get a science-fiction novel that was also longlisted for the Booker, as this was. The question, though: is it science fiction?

It certainly has science: most notably marine biology. Also space travel to the edge of the solar system via a new, unexplained drive; something which might be a first contact event; possible time travel; and a kind of ascendence. In fact there’s a section near the end that had strong resonances of 2001: A Space Odyssey for me.

So yes, it’s SF. But it feels somehow incomplete. Not unfinished, except in the way you might say that about 2001 itself. It keeps the pages turning OK, but I’m not entirely sure exactly what it’s trying to achieve, and (therefore) whether it’s successful.

It tells two stories at once. And I do wonder whether MacInnes was similarly torn between his desire to write a mainstream, literary novel, and one diving deep into fantastika.

Leigh, the marine biologist who ends up on a space mission, had a physically abusive father, which not surprisingly affects much of her life. Though her sister appears not to have suffered similarly, and there are hints that Leigh is not entirely a reliable narrator. (But then again, who is?) The adult Leigh is torn between her career and her desire to visit her mother, who is showing signs of dementia.

As a marine biologist Leigh experimentally engineers algae which is intended to feed, oxygenate, and cheer up the small crew of a year- (or more) long voyage. But there’s a lot going in the background of the story, that Leigh and most of the other characters are not privy to. Secrets kept by companies and governments. We, the readers, are also kept outside the walls of secrecy.

So it’s very good at evoking the situation of someone who is a cog — albeit an essential one — in very complex machine, but who has no picture of the machine as a whole.

All of which leaves it convincing, but frustrating, especially if you’re looking for a nicely wrapped-up story.

📗 Books 2025, 18: Glory Road, by Robert A Heinlein

I had a sudden hankering to reread this old Heinlein book (even older than me, it turns out, being first published in 1963). I read it as a kid, from the library, and if I ever bought a copy it isn’t accessible now.

I searched my local library’s catalogue. No joy. But the excellent World of Books duly had an old copy or two, and one was soon here.

It is almost exactly as I remembered it, which is to say it’s a tale of derring-do, sword-and-sorcery adventure, where the sorcery is sufficiently-advanced technology. We don’t learn anything about how it works, and it doesn’t matter. It’s just a fun story, very much of its time.

The first-person male protagonist is one of those highly-capable men beloved of that era’s male American SF writers. But he is relatively lacking in self-confidence at times, which is surprisingly refreshing for the type. The female lead is mostly great, and considerably more capable than the guy, even if he doesn’t exactly realise it.

Anyway, loads of fun, and I’m glad to have read it again after all these years.